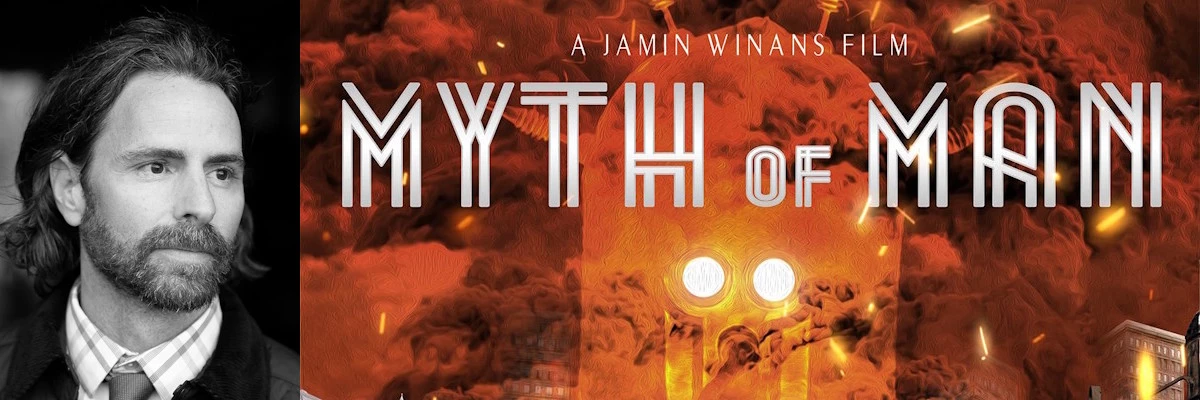

Jamin Winans talks Myth of Man

Ten years after releasing his last feature film, Jamin Winans returns with Myth of Man, and it's more than just a return to form. Myth of Man is his most ambitious and accomplished film to date, so I was delighted when he agreed to another interview. I was able to ask him how he collaborated with his wife on his films, how he got these ambitious projects funded, and where he kept finding the inspiration and drive for creating these unique films. If you want to know what it's like to pour your heart and soul into your passion and art, just continue reading.

Niels Matthijs: After a rather long hiatus (not counting your documentary), what pushed you to return to directing feature films?

Jamin Winans: We were actually never on hiatus, it just took a very long time to make Myth of Man. The script, the storyboarding, prep, shoot, post. It was just Kiowa and me, 95% of the time doing nearly everything. What you don't have in money, you make up for in time.

I've read that funding Myth of Man wasn't easy and required some personal sacrifices. How do you even budget a film that was obviously quite risky to make, especially when your own money is in it?

It's nearly impossible to know a proper budget for our films. Yes, we're making sci-fi, which should be very marketable and sellable, but it's not your grandma's sci-fi. An enigmatic sci-fi film without dialogue is uncharted territory, so we had to assume we weren't going to make much money. We had a few friends and previous investors come back and help, but we made it clear that they were investing in essentially a piece of art that may never make them a cent. We didn't ask for much. Instead, Kiowa and I sold our house and self-funded a majority of the film.

We had a plan to keep the budget very tight and mostly shoot guerilla-style on the streets of Budapest, Hungary, and supplement with VFX. We did exactly this and shot for six weeks (about 40% of the film) when we began having significant issues with a cast member. It was clear we weren't going to make it through the entire shoot, and we had better pull the plug before we lost any more money. In the end, we weren't able to use 99% of the footage we shot. That was 2019.

So we came back to the States, regrouped, and decided to change our strategy. Our original plan (shooting in real locations) was going to involve incredible amounts of rotoscoping (cutting the actors out from the background frame by frame) to build the world we wanted to create. And shooting guerilla-style in a city just doesn't give you the control you want. So we decided to restart and shoot the film entirely on a green screen stage that we built ourselves. We used a greenhouse frame and used frosted plastic over the top to create soft natural light. It was 96 feet by 40, and we shot almost the entire film in that space using no lights, much like was done in the early silent era.

Consequently, the budget ballooned after the financial loss in Budapest. Fortunately, our crew was only five people (including Kiowa and I) and we were able to keep things cost-effective. But again, what we didn't have in budget, we made up for in time. The film has over 3,500 VFX shots in it and it took us three and a half years to complete with just Kiowa, myself, and part time help from a Brazilian friend, Danilo Raele.

Kiowa (your wife) is very much involved in everything you made since Spin. How is it to work with your wife and how do you divide the work/credits?

Yes! 20 years now. Kiowa is the educated one with a law degree, and I'm the (barely) high school graduate with too much optimism. Early on, before we were even married, she took pity on me and started helping me with the legal side of running a business. When we got married, I think she realized just how helpless I was and jumped in on every aspect. She very quickly became an amazing producer, and on our films "producer" basically means doing everything. Over the years, she's taken on one task after another. She's been completely fearless, including becoming a production designer, costume designer, sound designer, and VFX artist among other things. I'm a writer and director, but I'm also the editor, composer, and various other jobs we can't afford to pay for.

We've always worked really well together. A lot of that has to do with mutual respect, and we just keep each other laughing. I understand what her strengths are, and she understands mine, so we defer accordingly.

You wrote the film yourself, where did you find inspiration for the setting, the characters, and the legends/lore that live within the movie's universe (the latter giving me Cartoon Saloon vibes)?

I started writing Myth of Man, wanting to tackle the subject of mortality and the space between life and death. Seems like every movie we've made starts with just a single image I have in my mind that emotionally moves me. With Myth I just had an image of a woman in a dark tunnel full of paper images flying by her and getting sucked up into a black vortex. I start with that single image and start asking questions. Those questions led me to what her situation was and how she got there.

The film was not originally going to be a silent film, but because the lead character, Ella, couldn't speak or hear, I found myself wanting to just see (and hear) the world from her perspective. I'm a big silent film fan and I loved the artistic possibilities of that. So the silent era came in as an influence. I'm a big fan of Eisenstein, Murnau, Lang, and of course Chaplin, so those influences can all be seen here.

The world-building largely came over several years. We knew we wanted it to feel set in the past as well as the future, which naturally lands you in a steampunk-like world. The music and sound design were all created with that past/future aesthetic in mind as well.

It's undeniable that familiarity is an easy way to avoid risk and makes it easier to secure a decent-sized audience, but for fantasy in particular, it feels like such a waste of potential. Myth of Man is a film that establishes a unique universe of its own, did you ever fear it would alienate audiences too much?

We knew from the beginning that Myth of Man would be a big risk both artistically and commercially. We've had our opportunities to be part of the studio system, but our attitude is very sincerely that life is too short. We have a very finite number of years on this Earth, and every film (independent or studio) takes a minimum of 1-2 years of your life. Neither Kiowa nor I want to waste a second making something we weren't intended to make. Consequently, that means we're usually working on low budgets and working ourselves to the bone. And yes, that may alienate some of our viewers, but it's probably not worth making if it doesn't.

With this being a silent film, how big of a challenge was it to communicate the more intricate details of the universe you created? And would you go through that again, or was this a one-time experience?

I had made a couple of silent short films years ago and quite enjoyed it. However, something of this scale was a whole other beast. You, as a cinephile, probably appreciate more than most how difficult that is. I spent three years on the script, and a lot of that was juggling how to convey certain ideas entirely with visuals, sound design and music. I composed the music while I was writing the script and that informed much of what the film is.

I do love and hate the constraints of not using dialogue. It forces you into new territory as a storyteller and artist, and I love that. But stay tuned as to whether or not we do it again...

I noticed in the credits that there's an entire section dedicated to the CG origins. I also saw that you and Kiowa were actively involved in the CG work. How did you accomplish such a CG-heavy film with such a small crew?

I've been doing VFX work for a long time, but Kiowa had no experience in it. My plan was to do a good deal of the VFX myself, but Kiowa being Kiowa taught herself the 3D program Blender using nothing but YouTube tutorials, and we quickly became a two-person VFX house. I mentioned the 3,500+ VFX shots. That meant I would key and rotoscope every shot, track it in 3D, then give the shot to Kiowa, who built the world in Blender, then gave me back those elements. I then composited those layers together, added ambience, additional lighting, and color, and walla! Eventually, we got our friend Danilo involved, and he helped us with a lot of keying and roto work as well as some After Effects work and design.

The credits you see in the end are all the different artists from around the world who modeled or photographed the 3D photogrammetry in the film. So various buildings, streets, and objects were created by combining the work of hundreds of different artists who made their objects available. Kiowa used these objects, modified some of them, created some of her own, and put them together like Legos to create our world.

One of the biggest selling points for me was the score. It's a personal pet peeve for sure, but for a silent movie, it's a crucial replacement for dialogue. I know music has always had a special place in your films, but I'd never seen it so tailored. How did that process go?

Thank you! I always say we get the best composer that we can afford on our zero dollars, so that's me. Some of that score are pieces I started working on 10 years ago when Myth was just a seed of an idea. Working out the tone musically really helps me tell the story. So the process is I would get stuck on the script and turn to the music, and that would inspire me and take me further. Then I would get stuck on music and turn back to the script. It's a good way to keep working even if you have a block. We only actually used about 10% of the music written for the film, maybe we'll put out a B-sides someday.

Music aside, silents are also characterized by expressive acting, and you struck gold with Laura Rauch. She has a relatively limited résumé, so how did you find her?

Laura really was a miracle. We found her originally on an online casting site. We had watched her reel and a couple of short films she was in, and we loved her. So we put her on our list. We knew Martin Angerbauer and had already cast him to play Boxback and it turned out he coincidentally knew Laura very well. He was a huge fan and convinced us to talk to her. We didn't even have a proper audition, we just talked to her and looked at her past work and knew she was the one. Turns out we were right.

What works so well is that Laura, much like Ella, is incredibly sweet, jovial, and optimistic, but she's also a hell of an actor. She hadn't done a ton of film, but she was very seasoned and well-respected in theater. All of our actors, with the exception of Ian Hinton (the little boy), had plenty of stage experience, and that was key on this film. Anthony Nuccio who plays Seeg made a great observation that the greenscreen was just like playing in black box theater, a situation in which you have to imagine a whole world around you.

Myth of Man took a long time to make, and you'll probably want to enjoy the fruits of all that labour for a bit, but do you have any concrete plans for the future? Any new ideas you want to turn into a film?

It's funny, I remember the last time we did an interview together for our film The Frame. You asked me then about our future film, and I don't think either one of us dreamed it would be 10 years to get there. That said, yes, we do have plans for the next one. We're still very focused on the release of Myth and want to see it flourish. Once we feel like it's on its way, we'll both probably take a very long nap and then jump into the newest creation.

Do you have any goals for this film? What would be your dream result once the floodgates open and the film is available to the masses?

We ultimately just hope each of our films has a long life. Myth of Man has gone quite well as we've toured with it, and it's getting out there. But ultimately it's not about how fast it jumps out of the gates, but more about whether or not it endures with an audience. There have been a lot of fans who really get this film deeply, and we're so happy for that. Hopefully that continues to expand.

Directors are also given the chance to ask questions they've been dying to see answered, which I will then try to answer to the best of my ability. Since there's so much one-way communication happening between creators and their audiences, I figured it might be interesting to see what would happen if the tables were turned.

Jamin Winans: Now my question for you Niels - As someone who watches more films (and very unique films) than anyone I know, where do you see cinema heading in the future, both artistically and commercially? Where do you hope it goes?

Niels Matthijs: After more than two decades of dedicated cinephilia, I don't think there are many big shifts ahead of us. I used to be a bit more optimistic that technology would have a significant and positive impact on distribution and I used to believe broader availability would result in better opportunities for smaller filmmakers, but in the end, the movie industry is like most other industries. Its main focus lies with making money, not art, which is just a byproduct. Sure enough, there are waves and balances may shift a little, but looking ahead another 20 years, I don't think cinema will have changed all that much. There will still be blockbusters, there will still be indie films, and most of them, regardless of which side they're on, will follow formulas that have the biggest chance of making their money back.

Artistically speaking, I do expect a lot from current AI trends. I know many artists will be mad when they read this, but AI art has been making tremendous strides, especially in the areas I tend to love (fantasy, sci-fi, surrealism, absurdism, ...). At the expense of giving up full control, I think it has the ability to unlock worlds and visions that are different from what the human mind would conjure. Combined with reduced cost and technical proficiency, I think this could allow artists to more easily express singular visions. But I'm purely talking potential here, once AI becomes the norm, I'm sure it'll be reined in by the big companies so they can profit from it.

As for hopes, as a fan of unique and off-kilter cinema, I can only hope that it will somehow become easier to watch the films I want to see. Availability is still one of the biggest issues, with many films stuck in festival circuits, geolocked behind borders, and/or lacking translation options. The hurdles you have to jump through to watch certain films as a film fan are often insane. I don't doubt interesting films will continue to exist, it's getting to them that's usually the most frustrating part.